Heresy and Heretic

Introduction

- Definition of Heresy

- Definition of the Heretic

- Distinctions

3.1. Formal/Material Distinction

3.1.A. Formal Heretic

3.1.B. Material Heretic

3.1.B.1. Common opinion: they are separated from the Church

3.1.B.2. A less common opinion (Bellarmin, Suarez, Wernz-Vidal, etc.)

3.1.B.3. Reconciling the two opinions

3.1.C. Objections

3.1.C.1. From modernist theologians

3.1.C.2. “A formal declaration is necessary”

3.1.C.3. Material heresy could be excused

3.2. Additional Distinctions

3.2.1. Public vs Occult

3.2.2. Positive vs Negative

3.2.3. Internal Forum vs External Forum

4. Treatment of the Material Heretic

4.1. Excommunication: No “latae sententiae” excommunication

4.2. Loss of Office “Ipso Facto” ?

5. Canonical Consequences for the Formal Heretic

6. Theological Foundation of this Distinction

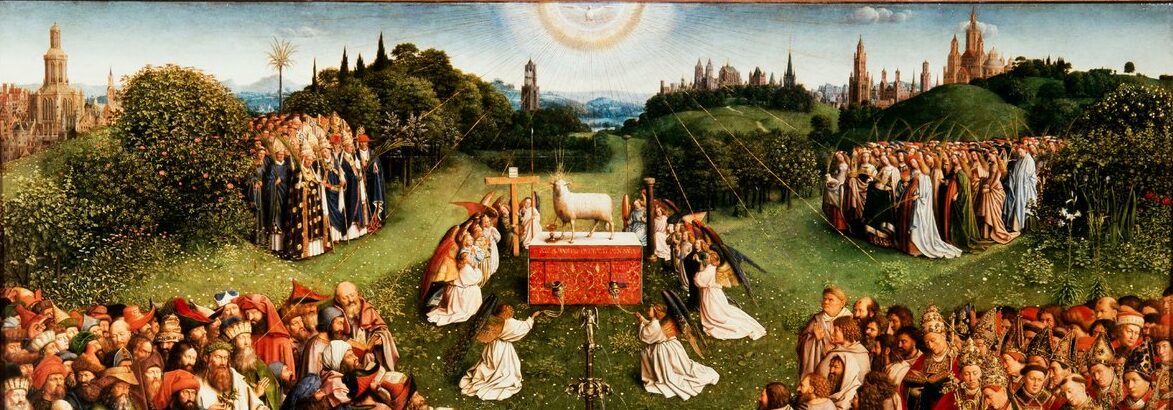

7. Here is a diagram of the various situations of heretics

8. Degree of Errors or Opposition to the Faith: Theological Notes or Censures

9. Semi-Heresy and the Semi-Heretic

9.1. Semi-Arianism (IVth century):

9.2. Semi-Pelagianism (Vth century):

9.3. Semi-Nestorianism and the Three Chapters (Vth-VIth centuries):

9.4. Pope Honorius I (VIIth century):

9.5. The Infallible Formula of Pope Hormisdas as Crucial Guide

9.5.1. This Formula is of great authority…

9.5.2. Application to Contemporary Situations

9.5.3. The example of the FSSPX

9.6. Refutation of Counter-Arguments

9.7. Brief

- The Bull Cum ex apostolatus officio

10.1. Its Text

10.2. Reconciliation with Traditional Doctrine

10.2.A. Presumption of Pertinacity

-

- All

- The Clerics:

10.2.B. Material Heretic and Sanctions:

10.2.C. Context of the Bull

- Practical Distinction between Formal and Material Heretic

11.1. Verification of the Error:

11.2. Evaluation of Publicity:

11.3 Canonical Admonition:

11.4. Context and Circumstances:

11.5. Practical Example:

- Current Catholic Perspective (Sedevacantist)

- Counter-Arguments and Refutation

13.1. The bull includes material heresy…

13.2. Without legitimate authority post-1963..

- Conclusion

- Sources

Introduction

The terms “heresy” and “heretic” possess precise definitions, both theological and canonical, with an essential distinction between the formal and material notions. This study treats the question of heresy and that of heretics as a single whole, for it is impossible to separate them without risking unnecessary repetitions. Moreover, theologians have always studied them simultaneously. It is appropriate, however, to distinguish the dogmatic problem — which relates to heresy considered as doctrine —, the moral problem — which relates to heresy considered as sin — and the canonical problem — which relates to heresy considered as a delict.

The first problem concerns heresy considered objectively. In the other two, heresy is considered formally. Indeed, in Catholic theology, material heresy is an objective error against the faith, but without subjective culpability — for example due to invincible ignorance. Formal heresy, on the other hand, involves a conscious and voluntary obstinacy, which makes it sinful on the moral plane and punishable on the canonical plane.

This doctrine, immutable and defined before 1963, rejects any subsequent deviation as contrary to the apostolic faith. Theologians affirm that heresy — especially formal — entails the automatic loss of any ecclesiastical office, rendering the See of Peter vacant since the heretical innovations of Vatican II.

The question of whether a public heresy, whether formal or material, entails ipso facto sanctions, such as excommunication or loss of office, is crucial for understanding the protection of the Catholic faith and ecclesiastical discipline.

According to the immutable doctrine of the Catholic Church, founded on the Scriptures, the Fathers, the Doctors, the ecumenical councils, and the 1917 Code of Canon Law, a fundamental distinction exists between formal heresy, characterized by voluntary pertinacity, and material heresy, devoid of pertinacity and due to invincible ignorance.

The bull Cum ex apostolatus officio of Paul IV (1559) seems to impose ipso facto sanctions for any public heresy, raising a question about its application to material heretics. This development clarifies this doctrine, explains how to practically distinguish the formal heretic from the material heretic in the case of public heresy, and reconciles the bull with traditional theology. Indeed, the Bull of Paul IV declares any office lost for any heretic, while the Tradition distinguishes formal and material heresy and does not admit the loss of office for a material heretic.

How to reconcile a disciplinary bull, considered in its included doctrine as infallible, with the constant and unanimous Tradition, which is also infallible?

- Definition of Heresy

In the 1917 Code of Canon Law, the definition of heresy is not found directly, but it derives from that of the heretic, as exposed in canon 1325 § 2 (Latin): “Post receptum baptismum si quis, nomen retinens christianum, pertinaciter aliquam ex veritatibus fide divina et catholica credendis denegat aut de ea dubitat, haereticus est.” Translation into English: “After having received baptism, if someone, while retaining the name of Christian, obstinately denies or doubts a truth that must be believed by divine and Catholic faith, he is a heretic.”

The definition of heresy is therefore: “Heresy is the act, by a baptized person claiming to be Christian, of denying or doubting with obstinacy a truth that must be believed by divine and Catholic faith.” Heresy is thus a grave doctrinal error that contradicts a dogma of faith defined by the Church.

In theology manuals, it is classically given as follows: “Haeresis est error circa fidem, quo quis, post baptismum susceptum, aliquam veritatem de fide divina et catholica pertinaciter negat vel pertinaciter dubitat.” (Translation: “Heresy is an error concerning the faith, by which someone, after having received baptism, obstinately denies or doubts a truth of divine and Catholic faith.”)

According to the Dictionary of Catholic Theology (art. Heresy, vol. VI, col. 2211, ed. 1912): “A doctrine that opposes immediately, directly, and contradictorily the truth revealed by God and authentically proposed as such by the Church.” That is, an error (obstinate or not, formal or material) against a truth of divine and Catholic faith.

Historical examples of heresies: Arianism (denial of the divinity of Christ, condemned by Nicaea in 325), Pelagianism (denial of original sin, condemned by Carthage in 418), or Modernism (condemned by Pius X in Pascendi Dominici gregis, 1907: “Modernismus est veluti collectum omnium haeresium”: “Modernism is like the collection of all heresies”).

Refutation of modernist counter-arguments: Some post-1963 claim that heresy is “relative” or “interpretive,” allowing “developments” that contradict prior dogmas. This is refuted by Vatican I (Dei Filius, cap. 4): “III. Si quis dixerit, dogmata ab Ecclesia proposita posse aliquando secundum progressum scientiae a sensu diverso recipere quam quo illa intellexit et intelligit, anathema sit” (“III. If anyone says that it can sometimes happen, according to the progress of science, that dogmas proposed by the Church must be given a different sense from that which the Church has understood and understands; let him be anathema.”), as demonstrated by Kleutgen (Theologia Wirceburgensis, 1880, vol. I) that the unity of faith requires the immutability of dogmas against any contrary evolution.

- Definition of the Heretic

As we have just seen, a heretic is a baptized person who commits a heresy. The heretic is a baptized person who, while retaining the name of Christian, denies with pertinacity (obstinacy) or doubts some truth of faith that must be believed by divine and Catholic faith. This is the classical definition, accepted by all theologians. It is already found in Saint Jerome (In Tit., III, 10), in Saint Augustine (De haeres., n. 88), in Saint Thomas (II-II, q. 11, a. 1), and it is formulated juridically in the Code of Canon Law, can. 1325, § 2.

The Vatican Council I (sess. III, cap. 3 on faith and reason) declares anathema those who deny that a truth can be revealed: “Si quis dixerit, rationem humanam ita independentem esse, ut fides ei a Deo praecipi non possit, anathema sit.” (“If anyone says that human reason is so independent that faith cannot be commanded to it by God, let him be anathema.”) In another article, Saint Thomas (Summa Theologiae, II-II, q. 5, a. 3) teaches the same thing by saying that he who obstinately denies the truth of a single article does not have faith, even for the other articles, but is unfaithful. The 1917 Code of Canon Law (canon 1325, § 2) stipulates in fact: “Post receptum baptismum, si quis, pertinaciter, dogma catholicæ fidei denegat vel de ea dubitet, est hæreticus” (“After baptism, he who denies or doubts with pertinacity a dogma of Catholic faith is a heretic”).

Heresy is therefore a fault against the faith. It consists essentially in the free choice of an opinion in opposition to the revealed teaching. It is a sin and a delict. It excludes from the communion of the Church, even before any sentence of excommunication and loss of office in the Church.

- Distinctions

3.1. Formal/Material Distinction

3.1.A. Formal Heretic

This is the one who, knowing that a truth is revealed and defined by the Church, freely and obstinately rejects it. “Est hæreticus formalis, qui veritatem revelatam, pro tali cognitam, pertinaciter negat” (“Is a formal heretic he who obstinately denies a revealed truth, known as such”) (Dictionary of Catholic Theology, art. Heresy, vol. VI). He is fully guilty, a sinner, and excommunicated “latae sententiae” (canon 2314, § 1), losing all office ipso facto (canon 188, § 4), as taught by Wernz-Vidal (Ius Canonicum, 1933, vol. VII) that the public and notorious heretic loses his office by full right, without any declaration.

Conditions:

– Valid baptism: Only the baptized can be heretics, for they are bound to the Catholic faith (canon 1325), to know it and hold it.

– Material object: The rejection or doubt must concern a dogma “de fide divina et catholica” (Vatican I, Dei Filius, cap. 3): “Fides est assentire Deo revelanti.” (Faith is assent to God revealing).

– Pertinacity: A constant and voluntary opposition is required for formal heresy, absent in the material case, as demonstrated by Franzelin (op. cit.) that pertinacity is required for the formal crime.

Formal heresy is the obstinate rejection or doubt, after baptism, of a truth revealed by God (in Scripture or Tradition) and proposed as to be believed “de fide” by the infallible magisterium of the Church (council, ex cathedra, or ordinary universal teaching). It involves:

– Full awareness of this revealed truth, accepted by the faith of the baptized, as explained by Saint Thomas Aquinas (Summa Theologica, II-II, q. 4, a. 1): “Fides est habitus mentis, qua inchoatur vita aeterna in nobis, faciens intellectum assentire non apparentibus.” (Faith is a habit of the mind, by which eternal life is begun in us, making the intellect assent to what is not apparent). The heretic must have been exposed to the revealed truth, either by the teaching of the Church or by a formal admonition.

– A voluntary error: a deliberate assent to a proposition contrary to Revelation, with knowledge of its contradiction. He must knowingly and freely choose to oppose this truth, through pride, bad will, or attachment to a personal opinion.

– “Pertinacity”: a voluntary resistance to the correction of the Church. This obstinacy must persist even after a clear correction or warning from ecclesiastical authority. For example, canon law (1917, canon 2314) stipulates that for an individual to be considered a heretic (formal), he must persist in his error after one or two formal admonitions:

Ҥ1. All apostates from the Christian faith, all heretics or schismatics and each of them:

1° Incur ipso facto an excommunication;

2° If after admonition, they do not come to repentance, let them be deprived of all benefice, dignity, pension, office or other charge, if they had any in the Church, and let them be declared infamous; after two admonitions, those who are clerics must be deposed.”

Potential counter-arguments and refutation:

Post-1963 innovators claim that the formal heretic requires an “official declaration,” but this is refuted by Cum ex apostolatus officio (Paul IV, 1559): “Si quilibet[…] in haeresim inciderit[…] ipso facto absque aliqua declaratione privatus existat” (“If anyone[…] falls into heresy[…] he is, ipso facto, without any declaration, deprived [of his office]”). As Bellarmin affirms (De Romano Pontifice, book II) that a manifestly heretical pope ceases ipso facto to be pope and head of the Church. We will see later that in practice some declarations are made, if chaos in the Church is to be avoided.

3.1.B. Material Heretic

The one who rejects a truth of faith without knowing that it is revealed and defined, through ignorance or non-voluntary error. “Est hæreticus materialis, qui eam ignorantiae vel erroris causa negat” (Dictionary of Catholic Theology, ibid.). He is in error objectively, but without subjective culpability or pertinacity.

Material heresy is an error on a defined point of doctrine, but without deliberate intention or clear knowledge of opposing the Church. It occurs:

– Through invincible ignorance or sincere error, without formal culpability or pertinacity, as explained by Franzelin (Theses de Ecclesia Christi, 1876) that material error is that which comes from invincible ignorance or invincible error.

3.1.B.1. Common opinion: they are separated from the Church

For membership in the Church, there is an important theological opinion (not certain, but common).

This most common opinion is that public material heretics are also (like formal heretics) separated from the Church, even without formal pertinacity, due to the external violation.

Shared by many theologians, this position relies on the fact that the Church, a visible society, requires not only baptism but also an external profession of the true faith (Pius XII, Mystici Corporis, 1943, n. 22)

And membership in the visible Church also requires objective adherence to the doctrine of the Church. Public error, even involuntary, breaks the visible unity.

Gerardus Van Noort, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, Bussum (Volume 1), 1920, p. 151:

“It is certain that public and formal heretics are separated from membership in the Church. The most common opinion is that public and material heretics are also separated from the Church.

For external membership requires not only external signs of faith and communion, but a true profession of the Catholic faith; now, he who publicly professes a heresy, even material, no longer professes the Catholic faith.”

Thus:

– the public material heretic is separated from the visible Body,

– but he can belong to the soul of the Church if he is in grace.

It is a juridico-sociological separation, not moral or penal.

This common opinion is shared with Card. Billot, Journet, etc.

Therefore, if someone externally professes a heretical doctrine, even through ignorance, he no longer externally manifests the true faith, and is thereby separated from the visible Body (not guilty, but objectively outside the visible society).

However, this is not certain doctrine, but the most common opinion; the certain doctrine requires pertinacity for the crime of heresy.

3.1.B.2. A less common opinion (Bellarmin, Suarez, Wernz-Vidal, etc.)

These authors maintain that membership in the visible Body is lost only by voluntary and notorious rupture (obstinacy).

The good-faith public material heretic remains a member of the Body, for he has not willed to separate from the visible authority or from the unity of communion.

Saint Robert Bellarmin (De Ecclesia militante, cap. 3) says explicitly:

“Haeretici qui per ignorantiam aliquid credunt contra doctrinam Ecclesiae, non sunt propter hoc haeretici, nec ab Ecclesia separantur.”

“The heretics who, through ignorance, believe something against the doctrine of the Church, are not for that reason heretics, nor separated from the Church.”

3.1.B.3. Reconciling the two opinions:

It is perhaps very appropriate here to make another distinction, already mentioned above, namely between the body and the soul of the Church, between the visible members and the unknown members of the Church. This distinction especially appeared in relation to the baptism of desire: those sacramentally baptized constitute the body of the Church, persons of good will with the baptism of desire belong to the soul of the Church.

Similarly, one can affirm that material heretics do not belong to the body of the Church because they do not have its faith, but to the soul of the Church because they err in ignorance, and one cannot sin in ignorance, so insofar as they are in a state of grace, they unquestionably belong to the (soul of the) Church. Thus, one understands that some theologians say they do not belong and others that they do belong to the Church.

3.1.C. Objections:

3.1.C.1. Modernist theologians might affirm that the notion of heresy must be interpreted more broadly or less strictly, taking into account “doctrinal progress” or the “living sense of the faith.” This argument is invalid according to traditional Catholic doctrine, because:

- The Council of the Vatican (1870), cited above, explicitly rejects the idea that the sense of dogmas can change over time.

- Saint Pius X, in Pascendi Dominici Gregis (1907), condemns modernism as a heresy that seeks to relativize dogmas under the pretext of evolution.

- Pertinacity, a key element of heresy, implies a conscious rejection, which excludes involuntary errors or subjective interpretations.

3.1.C.2. Some might argue that a formal declaration of the Church is necessary for a heretic to lose his office.

Refutation: Canon 188, § 4, and theologians like Wernz-Vidal and Bellarmin clearly affirm that the loss of office is ipso facto for a public and notorious heretic. No declaration is required, because public heresy is an objective act that breaks communion with the Church.

3.1.C.3. Material heresy could be excused, even in a cleric, due to invincible ignorance.

Refutation: For a cleric, especially a bishop or a pope, invincible ignorance is hardly admissible, because they have the obligation to know the Catholic faith. Moreover, public heresy, by its nature, implies an external manifestation that makes pertinacity presumed, unless proven otherwise.

3.2. Additional Distinctions

3.2.1. Public vs Occult

The “public” formal heretic manifests his error externally (words, writings, teachings) and is juridically sanctioned, losing his jurisdiction: Canon 2264: “Any act of jurisdiction, both in the external forum and in the internal forum, posed by an excommunicated person, is illicit; but if there has been a condemnatory or declaratory sentence, it is even invalid, except as prescribed in can. 2261, § 2.” The “occult” heretic keeps his error in his conscience without making it public; he is not treated as a heretic in the canonical sense, although his interior sin remains grave if it is formal, as explained by Prümmer (Manuale Theologiae Moralis, 1931, vol. I, n. 446) that occult heresy does not entail censures, but that it is internal. In any case, as formal, he deserves hell like any mortal sin.

3.2.2. Positive vs Negative

– Positive heresy: Direct rejection of a dogma (ex.: denial of transubstantiation).

– Negative heresy: Pertinacious doubt on a dogma, as defined by Billot (De Ecclesia, 1927, p. 634) that negative heresy is a persistent doubt concerning a dogma.

3.2.3. Internal Forum vs External Forum

An additional nuance on the internal vs external judgment of heresy — that is, the distinction between the internal forum and the external forum of the Church — according to pre-conciliar dogmatic theology manuals (ex.: Tanquerey, Synopsis Theologiae Dogmaticae, 1927, vol. III, n. 1245; Billot, De Ecclesia Christi, 1910, vol. I, p. 612): the internal forum concerns the sin of the soul judged by God or in confession, while the external forum belongs to the visible ecclesiastical judgment to sanction public error, thus limiting contagion without awaiting proven internal pertinacity.

The Church judges visible acts (external forum) to protect the common good, without claiming to probe internal intentions (internal forum), reserved to God or confession. The external forum concerns the ecclesiastical judgment aimed at limiting the contagion of public error (cfr. Catholic Encyclopedia, “Ecclesiastical Forum” — definition of the external forum and internal forum).

- Treatment of the Material Heretic

Unlike the formal heretic, the material heretic does not incur the same automatic sanctions, because he lacks pertinacity and subjective culpability.

The material heretic, in the external forum, is not presumed pertinacious until the matter is established. Here are the details of his status:

4.1. Excommunication: No “latae sententiae” excommunication:

Automatic excommunication (canon 2314, § 1) applies only to the formal heretic, because it requires voluntary pertinacity. The material heretic, acting through ignorance or sincere error, is not considered a conscious rebel against the Church (Cardinal Billot, De Ecclesia Christi, 1927, vol. I).

4.2. Loss of Office “Ipso Facto”? : According to the 1917 Code, the loss of an ecclesiastical office (canon 188, § 4) or the incapacity to receive one (canon 2314, § 1) applies to clerics who commit grave delicts, such as public heresy and notorious. However, for the material heretic, this sanction does not apply automatically:

– If he holds an office (priest, bishop, etc.) and professes a material heresy without making it public, he retains his office as long as his error remains occult or not judged by ecclesiastical authority.

– If his error becomes public (for example, by teaching an erroneous doctrine without knowing it is heretical), a trial or admonition is required to establish his intention. Without proven pertinacity, he does not lose his office ipso facto, but a ferendae sententiae sentence can limit his ministry.

4.3. Removal to Protect the Faithful?

The material heretic is not systematically removed from the Church to “not contaminate the other faithful,” unlike the public formal heretic, of whom Saint Thomas says: “After the first and second admonition, avoid the heretic” (Summa Theologica, II-II, q. 11, a. 3): “Post primam et secundam admonitionem devita haereticum.” However, if the material heretic spreads his error (for example, by preaching or publicly teaching a false doctrine, even without malice), the Church must intervene to limit his influence:

– A formal admonition must be addressed to him to limit his teaching: Canon 2315, suspect of heresy: “Suspectus de haeresi, qui monitus causam suspicionis non removeat, actibus legitimis prohibeatur, et clericus praeterea, repetita inutiliter monitione, suspendatur a divinis; quod si intra sex menses a contracta poena completos suspectus de haeresi sese non emendaverit, habeatur tanquam haereticus, haereticorum poenis obnoxius.” (“To the suspect of heresy, who after admonition does not remove the cause of suspicion, let the legitimate acts be forbidden; if he is a cleric, moreover, after a second useless admonition, let him be suspended ‘a divinis’. If within six months completed after having contracted the penalty, the suspect of heresy does not amend himself, let him be held as a heretic, subject to the penalties of heretics.”)

– If he persists after being instructed, his ignorance ceases to be invincible, and he becomes a “formal heretic,” then incurring the full sanctions, as explained by Van Noort (Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, 1920) that the public material heretic can be admonished and restricted for the protection of the faithful.

– In practice, a public material heretical cleric can be suspended from his functions (by a “ferendae sententiae” sentence) to avoid confusion among the faithful, even without immediate excommunication, according to Billot (op. cit.): a public material error can be restricted due to scandal.

4.4. Correction and Instruction:

The preferred approach toward the material heretic is pastoral charity: he must be instructed and corrected to return to the truth. Some authors hold (against the common opinion No. 3 above) that as long as there is no pertinacity, he remains a member of the Church and can receive the sacraments (Prümmer and Noldin limit this to private receptions when no scandal appears), unless his public error causes a manifest scandal necessitating intervention, as demonstrated by Hurter (Compendium Theologiae Dogmaticae, 1907, t. III) that public material error must be restricted so that no scandal is caused.

4.5. Refutation of Modernist Counter-Arguments:

The post-1963 innovators claim that the material heretic is “always innocent” and deserves no measures, but this is refuted by Saint Pius X in Pascendi Dominici Gregis (1907), which condemns the idea that error, even material, can be tolerated when it corrupts the faith; in the current crisis, the errors of Vatican II, if propagated through ignorance, justify the rejection of the offices of the modernists to protect the faithful.

In short, we must clearly denounce all heresies, warn the faithful to protect them from material heretics, and separate from pertinacious (formal) heretics and note their ipso facto excommunications. The material heretic, even public, does not incur latae sententiae excommunication nor loss of office ipso facto, because he lacks pertinacity. However, if his public error causes a scandal (disturbance of the faithful), the Church must impose disciplinary measures (ferendae sententiae), such as a suspension, to protect the common good (see Msgr. Charles Journet, The Church of the Word Incarnate, vol. I, 1955).

- Canonical Consequences for the Formal Heretic

– Latae sententiae excommunication (canon 2314, § 1).

– Incapacity to receive or exercise an ecclesiastical office (canon 188, § 4), even for a pope, as demonstrated by Bellarmine (De Romano Pontifice, book II, cap. 30) that a manifestly heretical pope ceases ipso facto to be pope and head of the Church.

– Deprivation of the sacraments (except in danger of death, canon 2261).

– Loss of jurisdiction if the heresy is public and notorious (canon 2264).

– Explicit removal to protect the faithful, in accordance with Saint Thomas.

– Absence of ecclesiastical procedure: delicate question! Even though the Bull “Cum ex apostolatus officio” (Paul IV, 1559) and Saint Robert Bellarmine affirm that the manifest heretic loses the office ipso facto, some classical theologians (like Cajetan or John of Saint Thomas) insist on the necessity of a juridical ascertainment of public heresy to draw canonical consequences from it. Cajetan, in his Tractatus de Fide (1530), argues that, although heresy internally deprives of jurisdiction, an ecclesiastical declaration is required for external effects, to avoid chaos in the visible Church. John of Saint Thomas, in Cursus Theologicus (1643, disp. 20, art. 2), maintains that public heresy renders the pope ipso facto deposed, but an ascertainment by the cardinals or an imperfect council is necessary to declare the vacancy and proceed to an election. These opinions, although minority, offer a complete panorama, strengthening the sedevacantist argument by showing that even prudent theologians confirm the automatic loss, with or without formal procedure, in the face of a manifest heresy like that of Vatican II.

- Theological Foundation of this Distinction

– Saint Thomas Aquinas (Summa Theologica, II-II, q. 11): Formal heresy is a grave sin against faith, while material heresy is an error without malice.

For the material heretic, the absence of pertinacity distinguishes him from the formal, but his public error can justify an intervention, as taught by Billot (Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, vol. I, q. 14) that the material heretic is not considered as rebellious to the Church. According to Saint Thomas Aquinas (Summa Theologica, II-II, q. 11, a. 2), formal heresy (heresy properly speaking) requires pertinacity, absent in material heresy: “Et ideo qui pertinaciter in errore circa ea quae sunt fidei versatur, ille proprie haereticus dicitur.” (“Thus, he who obstinately persists in an error concerning the things of faith is properly called a heretic.”)

– Saint Augustine (Contra Faustum, XX, 3): “Haereses autem et schismata hoc vitio non habent caritatem: haeresis falsa opinione, schisma dissensione propria.” (“Heresies and schisms are deprived of charity: heresy by a false opinion, schism by a proper dissension.”) defining heresy as separation from charity; intention determines culpability.

– The pre-1963 doctrine insists on the revealed truth and the unity of the Church: the material heretic is a case of errancy to correct, not rebellion to punish immediately, but limited if public.

- Here is a diagram of the various situations of heretics

- Material heretics:

- a)in terms of the external forum, they are ipso facto outside the Church

- Reason: by heresy, they no longer have the faith of the Church

- Explanation: to be a member “(of the Body) of the Church,” one must have the faith of the Church

iii. This is the most common opinion (Van Noort, Billot, Journet, etc.)

b)in terms of the internal forum, they can nevertheless remain members of the Church if they are in a state of grace, that is, belong to “the Soul of the Church”

i.Reason: He who sins through invincible ignorance is not guilty of that sin

ii.Explanation: he can be in a state of grace, if he has no mortal sin on his conscience otherwise

- c)no ipso facto excommunication

- d)no ipso facto loss of functions and jurisdiction

- e)they must nevertheless be admonished by the Church as quickly as possible

- f)Ecclesiastical authority can take measures to prevent their harmful influence on the community

- Formal Heretics (FH)

- a)If they are occult formal heretics(only in the internal forum), it is secret, unknown to the Church (for example, being a member of a secret heretical society)

- in the internal forum (before God and for their own conscience):

- loss of the state of grace

- ipso facto they are outside the Church

- if they are in charge, they are occult usurpers

- They know all this in their conscience, and they sin gravely, but since no one else knows, nothing happens in the external forum:

- in the external forum (for the Church)

1.they are members of the Church

2.No excommunication (because no one in the Church knows their crime)

3.No loss of functions and jurisdiction (because no one in the Church knows they no longer have jurisdiction)

- Jesus, Invisible High Priest, supplies (that is, adds) the missing jurisdiction to make the Church function,

- a)Reason: fidelity to His promise that the Church is indefectible

- b)Example: a pope secretly a member of a secret heretical society

- If their formal heresy, first secret, comes to be known after their death:

- Ipso facto separated from the unity of faith and, consequently, outside the Church, from the moment of their heresy, despite their heresy having been discovered only after death.

- No excommunication pronounced after their death, because the Church pronounces neither penalty nor juridical judgment on them, not judging the dead (“De mortuis Ecclesia non judicat”). This ascertainment therefore pertains not to the judicial forum, but to the doctrinal and historical forum: their works and doctrine are judged, and it is recognized that they were – for God – no longer members of the Church, without there being an ecclesiastical sentence.

- If, on the contrary, the proof of heresy is not certain but only probable, it is said that they are suspects of heresy, and not formally heretical.

- The Church being indefectible, all their actions and decisions remain valid for this reason. Because as already mentioned, the Bull of Paul IV applies, like any sanction of the Church, only to public formal heresies, never occult, by impossibility of sanctioning an unknown crime (before death)

- b)If they are public formal heretics (in the external forum): because they have publicly expressed a heresy and are obstinate

- Who:

- Laity who have been admonished once

- Clerics

- a)are presumed to know the faith, so are always formal heretics (common opinion)

- b)unless they prove they were ignorant (and that they are therefore material heretics)

- Consequences:

- Ipso facto outside the Church

- Ipso facto excommunication

- Ipso facto loss of functions and jurisdiction:

- a)For clerics who are formal heretics

- b)For clerics who have proven they were only material heretics: after having been admonished twice they lose their functions and jurisdiction, because then they become formal heretics

- Degree of Errors or Opposition to the Faith: Notes or Theological Censures

The theological notes of errors (also called negative theological censures) are the judgments made by the Church or theologians on erroneous doctrinal propositions, to indicate their degree of opposition to the faith or theology catholic. There is a traditional and precise classification of these censures, especially codified by scholastic theologians like Saint Robert Bellarmine, Melchior Cano, Domingo Bañez, John of Saint Thomas, Billuart, and synthesized in the 19th century by Adolphe Tanquerey in his Synopsis theologiae dogmaticae.

These notes protect the unity of faith against deviations, as explained by Franzelin in De Divina Traditione et Scriptura (1870s) that theological notes are qualifiers that indicate what type the error of a proposition is, and to what extent it diverges from the doctrine of the Church. In the current sedevacantist perspective, these notes confirm that the errors of Vatican II, such as religious liberty or ecumenism, are haereticae, entailing ipso facto the loss of any ecclesiastical office, rendering the See of Peter vacant, because any opposition to defined doctrine is a break with Revelation.

Number of theological notes of errors: There are 12 to 16 notes (depending on the fineness of the distinction), classified from the most serious to the least serious. Here is the classical list, following the order of decreasing gravity:

- Heresiarch / Formal Heretic:

Preliminary remark: this No. 1 designates a person and not a proposition. It is therefore not a note in the strict sense but a person in the highest degree of error.

Definition: He who denies a truth of faith defined as revealed by God and proposed as such by the Church, and who propagates it.

Latin Formula: Propositio haeretica a Persona haeretica formali.

Gravity: The most serious. This dissemination of supernaturally mortal error makes him so evil and dangerous to the highest degree. The proposition and this person are formally heretical. Separation from the Church.

Doctrinal and Canonical Implications: Implies pertinacity (obstinacy) and full awareness, leading to latae sententiae excommunication (canon 2314 § 1 of the 1917 Code) and ipso facto loss of office (canon 188 § 4).

Pastoral Judgment: Requires urgent doctrinal correction. If persistence after warning: formal heresy, loss of faith, separation from the Church.

Classical Theological References: Denzinger no. 3020 (Vat. I, Dei Filius); Tanquerey, Synopsis theol. dogmat., I, no. 76; Saint Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 11, a. 1-4.

- Propositio haeretica — Heretical Proposition

Definition: Proposition denying a defined truth of faith (dogma) — de fide definita.

Latin Formula: Propositio haeretica.

Gravity: Supreme. The obstinate refusal (after warning) constitutes a mortal sin against faith and falls under latae sententiae excommunication (cf. CIC 1917, can. 2314 § 1).

Doctrinal and Canonical Implications: Formally denies an article of faith defined by an ecumenical council or by the Sovereign Pontiff.

Pastoral Judgment: To condemn, especially in seminaries and teaching.

Serious danger for the faith; risk of evolution toward formal heresy.

Classical Theological References: Denzinger no. 3020 (Vat. I, Dei Filius); Tanquerey, Synopsis theol. dogmat., I, no. 76; Saint Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 11, a. 1-4.

- Proxima haeresi — Close to Heresy

Definition: Proposition that contradicts a revealed doctrine not yet solemnly defined, but proposed as such by the ordinary universal Magisterium.

Latin Formula: Proxima haeresi.

Gravity: Very serious; pre-heretical.

Doctrinal and Canonical Implications: Denies a de fide divina truth, taught unanimously by the dispersed bishops but united to the Pope (Magisterium ordinarium universale).

Pastoral Judgment: Correction formally necessary.

Grave danger for the faith; risk of evolution toward formal heresy.

Classical Theological References: Van Noort, De vera religione; Vatican I, Dei Filius, DS 3011; Msgr. G. Van der Vorst, Institutiones Theologiae Fundamentalis, 1923.

- Propositio errori haeretico proxima — Close to the Heretical Error:

Definition: Similar to a heresy in its formulation or consequences, without directly contradicting it.

Latin Formula: Propositio errori haeretico proxima.

Gravity: Very serious.

Doctrinal and Canonical Implications: Proposition that, if developed or maintained, logically leads to heresy.

Pastoral Judgment: To condemn, especially in seminaries and teaching.

Classical Theological References: Billuart, De Fide, diss. IV, art. IV; Gousset, Théologie morale, I, ch. IV.

- Propositio erronea — Erroneous: Definition: Contradicts a doctrine held as theologically certain, even if not revealed. Latin Formula: Propositio erronea. Gravity: Serious, but less than the previous ones. Doctrinal Implications: Goes against a certain conclusion, logically drawn from a dogma.

Pastoral Judgment: Can be tolerated in debate, but not in magisterial or catechetical teaching. Classical Theological References: Tanquerey, I, no. 76; Pesch, Praelectiones dogmaticae, I, no. 425.

- Propositio temeraria — Rash: Definition: Contradicts an opinion unanimously held by theologians or the ordinary teaching of the Church, without sufficient motive. Latin Formula: Propositio temeraria. Gravity: Less than formal error, but very imprudent. Doctrinal Implications: Undermines doctrinal unity; sign of intellectual pride. Pastoral Judgment: Attitude to correct among priests and teachers. Seed of future errors. Classical Theological References: Melchior Cano, De locis theologicis, lib. XII; John of Saint Thomas, Cursus theologicus, t. I.

- Propositio sapit haeresim — Savors of Heresy: Definition: Formula or proposition that smells of heresy, without being directly heretical. Latin Formula: Propositio sapit haeresim. Gravity: Medium to serious depending on the context. Doctrinal Implications: Can trouble the faith of the simple faithful. Often used against Jansenist or Lutheran propositions. Pastoral Judgment: To condemn, and prevent, especially in catechesis. Classical Theological References: Unigenitus (1713), many propositions are sapit haeresim; Denzinger 2420 sqq.

- Propositio suspecta de haeresi — Suspect of Heresy: Definition: Proposition that makes one suspect it contains a heresy, without being able to demonstrate it with certainty yet. Latin Formula: Propositio suspecta de haeresi. Gravity: Moderate.

Doctrinal Implications: Can serve to circumvent faith, weakens orthodoxy. Pastoral Judgment: To monitor, question the author, require clarification.

Classical Theological References: Saint Thomas, De Veritate, q. 14, art. 9; Auctorem fidei, 1794 (many propositions of the Synod of Pistoia).

- Propositio male sonans / Piarum aurium offensiva — Ill-Sounding / Offensive to Pious Ears: Definition: Proposition expressed in shocking, inappropriate, disrespectful terms, even if the substance may be orthodox. Latin Formula: Male sonans, offensiva piarum aurium. Gravity: Weak, but not negligible. Doctrinal Implications: Can shock, scandalize the faithful, even if the intention is orthodox. Pastoral Judgment: To reformulate, especially in sermons, catechisms and publications. Classical Theological References: Unigenitus (1713); Tanquerey, De locis theologicis, no. 42.

- Propositio scandalosa — Scandalous: Definition: Proposition that leads others to error, doubt, or sin, even if it is accurate in itself.

Latin Formula: Propositio scandalosa. Gravity: Variable, but potentially serious depending on the circumstances. Doctrinal Implications: Scandal is a sin against charity and prudence (cf. S. Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 43). A proposition can be objectively scandalous even if the intention is not bad. Pastoral Judgment: To proscribe, especially in publications and preaching; must be denounced in seminaries. Classical Theological References: Unigenitus (1713), number of propositions condemned as scandalosae; S. Thomas, Summa Theol., IIa IIae, q. 43, a. 1-7.

- Propositio schismatica — Schismatic: Definition: Proposition that contradicts the submission due to the Sovereign Pontiff or to the legitimate Catholic hierarchy. Latin Formula: Propositio schismatica. Gravity: Very serious, offense against the unity of the Church.

Doctrinal Implications: Schism is a voluntary break from submission to the supreme ecclesiastical authority. It can exist without formal heresy, but often leads to it. Pastoral Judgment: To condemn absolutely.

Implies the canonical penalty of latae sententiae excommunication (CIC 1917, can. 2314). Classical Theological References: Gratian, Decretum, C. 24, q. 1; S. Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 39; Denzinger 2598 (Cum ex Apostolatus of Paul IV, 1559).

- Propositio impia / blasphema — Impious / Blasphemous: Definition: Propositions injurious toward God, His holiness, His saints, His mysteries or His word. Latin Formula: Propositio impia, blasphema. Gravity: Very serious.

Doctrinal Implications: Direct offense to the Divine Majesty or to what is holy. Often used against blasphemies. Pastoral Judgment: To condemn without appeal. May require severe canonical penalties. Classical Theological References: Catechism of the Council of Trent, III, on the 2nd Commandment; S. Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 13.

- Propositio idolatrica / superstitiosa / magica — Superstitious / Magical / Idolatrous: Definition: Propositions that attribute to creatures or non-revealed practices a supernatural power. Latin Formula: Propositio superstitiosa, idolatrica, magica. Gravity: Very serious (direct violation of the 1st commandment).

Doctrinal Implications: Contradicts supernatural faith in God alone. Proposes a deviant religion. Pastoral Judgment: To extirpate. May require exorcism or canonical interdict. Classical Theological References: Catechism of the Council of Trent, on the 1st Commandment; S. Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 92-96.

- Propositio turpis / obscena — Shameful / Obscene: Definition: Immoral or immodest propositions, particularly on sexuality, sacraments or morals.

Latin Formula: Propositio turpis, obscena. Gravity: Morally serious, especially if stated publicly. Doctrinal Implications: The Church condemns all that offends purity. Pastoral Judgment: To censor formally. Can corrupt youth and scandalize. Classical Theological References: Leo XIII, Officiorum ac Munerum, 1897 (Index Librorum Prohibitorum); S. Alphonsus, Theologia Moralis, lib. IV.

- Propositio subversiva hierarchiae ecclesiasticae — Subversive to the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy: Definition: Propositions that deny or relativize the divine hierarchy of the Church, that is, the distinction between the pope, bishops, priests and faithful. Latin Formula: Propositio subversiva hierarchiae ecclesiasticae. Gravity: Very serious. Doctrinal Implications: Denies the divine institution of the power of jurisdiction and magisterium. This is the typical error of conciliarism or democratic modernism. Pastoral Judgment: To repress. Leads to Protestantism, Jansenism, or modernism. Classical Theological References: Vatican I, Pastor aeternus (DS 3050 sqq.); Syllabus Errorum (1864), errors 37-40. NB: This does not exist explicitly as such in the classical list. The traditional theological censure would rather be “erronea” or “haeretica” depending on the cases.

- Propositio seditionem parens — Bearing Sedition: Definition: Propositions that incite revolt against legitimate authority, ecclesiastical or civil, under pretext of religion. Latin Formula: Propositio seditionem parens. Gravity: Variable, but often serious. Doctrinal Implications: This is the doctrinal instrument of insubordination. Condemned by Saint Thomas as a grave sin against social and ecclesiastical peace. Pastoral Judgment: Must be corrected and prevented among faithful inclined to systematic criticism or doctrinal independentism.

Classical Theological References: Leo XIII, Immortale Dei (1885), on relations between Church and State; S. Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 42 (on sedition). NB: This is more a moral and political qualification than a classical theological note.

Classical References:

– Adolphe Tanquerey, Synopsis theologiae dogmaticae, t. I, no. 74–76.

– Billuart, De Virtutibus Theologicis, Dissert. V, art. 3.

– Jean de Saint-Thomas, Cursus Theologicus, t. I.

– Denzinger, Enchiridion symbolorum, intro on theological censures.

– Melchior Cano, De locis theologicis, livre XII.

NB: These exhaustive notes prove that Vatican II is heretical, confirming the Sede vacante. Final refutation: The post-1963 claim that the notes are “historical” or “non-applicable,” but this is refuted by Pius X (Pascendi: “Ambiguity modernist is heretical”), because they protect the immutable faith; Franzelin, o.c., writes that theological notes must be respected for the protection of the faith.

- Semi-Heresy and the Semi-Heretic

The study of semi-heresy constitutes an essential element of theological reflection within the Catholic Church. This term designates positions that are not fully heretical, but which weaken orthodoxy through ambiguities, compromises or favorable attitudes toward heretics, without explicitly embracing heresy.

According to the teaching of the Church Fathers and councils, and in accordance with the current sedevacantist view, it is appropriate to understand that semi-heresy occupies a dangerous gray area between the pure doctrine of faith and its complete rejection. This view, rooted in immutable Tradition, refutes counter-arguments that minimize semi-heresy as mere subjective interpretations, by pointing to objective condemnations in Church history. Such counter-arguments, often motivated by a desire for compromise with modern errors, are invalidated by the clear anathemas of councils and pontifical documents, which punish any form of complicity with heresy.

Another excess consists in considering semi-heretics as heretics. This will blur the understanding of the current situation of the Church because heretics (formal) are not members of the Church but semi-heretics always are.

Definition of Semi-Heresy According to the Teaching of the Church

Semi-heresy, as understood in theological tradition, designates a theological position that is not completely heretical, but which deviates from orthodoxy by favoring ideas linked to a heresy or by encouraging them. The prefix “semi-” implies an intermediate or ambiguous attitude, often oriented toward compromise, ambiguity in formulations or partial influence of heretics without adopting all implications. This differs from complete heresy, which consists in an explicit denial of a defined dogma, but is also condemnable because this undermines the purity of faith: and it can be “temeraria,” “male sonans,” “suspecta de haeresi,” or even “proxima haeresi.”

The Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) and pre-1963 sources, such as the writings of the Church Fathers, describe currents called ‘semi-Arians,’ ‘semi-Pelagians’ etc. These “semi-heresies” include elements such as: an attempt at reconciliation between orthodoxy and heresy; a doctrinal ambiguity allowing interpretations as heretical; or the facilitation of heresy by weakening orthodoxy. The Church has condemned historical currents qualified by authors as semi-Arians, semi-Pelagians, etc. on several occasions, because this threatened the unity of faith, as fixed in councils and pontifical bulls. Counter-arguments claiming that semi-heresies are just polemical labels are refuted by the objective criteria of the Church: if a position opens the door to heresy, it falls under anathema, regardless of intentions, as appears in the Formula of Pope Hormisdas (519), which pronounces anathema on heretics and their partners in communion.

Examples of Historical Semi-Heresy

The history of the Church offers numerous examples of semi-heresy, which illustrate how such positions have been condemned to preserve the integrity of doctrine.

9.1. Semi-Arianism (4th century): This group, also known as homoiousians, affirmed that the Son of God was “of similar nature” (homoiousios) to the Father, but avoided consubstantiality (homoousios) as defined at the Council of Nicaea (325). They sought a middle way between Arianism, which denied the divinity of the Son, and orthodoxy. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), their position was a compromise that weakened orthodoxy and was interpretable as favoring Arianism. Many of them, like the Macedonians, were condemned in councils, although some returned to orthodoxy under pressure from figures like Athanasius. Counter-arguments presenting semi-Arians as mere misunderstandings are invalidated by their condemnation at Nicaea and in subsequent synods, which qualified any deviation from homoousios as heretical.

9.2. Semi-Pelagianism (5th century): Appeared among monks in southern Gaul around 428, it attempted a compromise between Pelagianism, which denied the necessity of grace, and Augustine’s teaching on its absolute necessity. Semi-Pelagians recognized grace for salvation, but affirmed that man could take the initiative by his free will, without prevenient grace.

The Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) describes it as a doctrine that did not deny the necessity of grace, but exaggerated the role of human will, thus favoring Pelagianism. It was condemned at the Council of Orange (529), which confirmed Augustine’s teaching. Counter-arguments, such as those affirming that semi-Pelagians had orthodox intentions, fail because their position minimized universal original sin, which contradicts Tradition.

9.3. Semi-Nestorianism and the Three Chapters (5th-6th centuries): In the controversy over the Three Chapters (writings of Theodore of Mopsuestia, Theodoret of Cyrus and Ibas of Edessa), these authors were condemned by the Fifth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople II, 553), although they were not fully Nestorian. Their formulations, influenced by the School of Antioch, separated the natures of Christ too strongly, favoring Nestorianism. They were considered post-mortem as semi-heretical, because their ideas offered fertile ground for heresy.

9.4. Pope Honorius I (7th century): The Sixth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople III, 680-681) condemned Honorius post-mortem as heretical, because he favored the monothelete heresy by negligence: he “fanned the flame of heresy by his negligence,” without professing it formally. Pope Leo II confirmed this, noting that Honorius had allowed the immaculate faith to be sullied. Pre-1963 sources, such as Denzinger’s Enchiridion (editions before 1963), and the Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), recognize this as a case of semi-heresy, because it was not a formal ex cathedra declaration, but a weakening of orthodoxy. Counter-arguments from later interpretations, affirming that Honorius was not a true heretic, are refuted by the conciliar anathemas and Leo II’s confirmation, which show that negligence toward heresy is equivalent to favoring it.

These examples show that the Church has always condemned semi-heresy to maintain purity, in accordance with the Formula of Pope Hormisdas (519), which pronounces anathema on heretics and their partners in communion, echoing 2 John 1:10-11.

9.5. The Infallible Formula of Pope Hormisdas as Crucial Guide

A particularly important point in the study of semi-heresy is the Formula of Pope Hormisdas of 519, also known as Libellus Hormisdae, which contains an infallible doctrine and serves as a guide for behavior toward heretics and semi-heretics. This document, drafted by Pope Hormisdas (514-523) to end the Acacian schism, was a confession of faith that Eastern bishops had to sign to restore unity with Rome. The schism, caused by the Henotikon of Emperor Zeno in 482 and supported by Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople, had separated the Greek and Roman Churches by a compromise with monophysite tendencies, which undermined the Council of Chalcedon (451). After the death of Emperor Anastasius in 518 and the advent of the orthodox Emperor Justin I, the Formula was signed on March 28, 519 in Constantinople, restoring unity.

The text of the Formula emphasizes the necessity of preserving the rule of true faith and not deviating from the prescriptions of the Fathers. A key passage says: “Prima salus est, regulam rectae fidei custodire et a constitutis Patrum nullatenus deviare. Et quia non potest Domini Nostri Jesu Christi praetermitti sententia dicentis: Tu es Petrus et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam. Haec quae dicta sunt rerum probantur effectibus, quia in sede apostolica immaculata est semper Catholica conservata religio.” (“The first condition of salvation is to keep the rule of the right faith and to deviate in no way from what has been established by the Fathers. And because the sentence of Our Lord Jesus Christ cannot be ignored: ‘You are Peter and on this rock I will build my Church’ [Matthew 16:18]. These words are proven by the facts, for in the Apostolic See, the Catholic religion has always been preserved immaculate.”) Then follows the anathematization of heretics such as Nestorius, Eutyches and others, including Acacius: “Nos pariter Acacium quondam Constantinopolitanum episcopum eorum socium et participem anathematizamus, una cum his qui in eius communione perseverant; QUIA COMMUNIONEM ALICUIUS AMPLEXARI, SIMILEM MERERI SORTEM EST.” (“We likewise anathematize Acacius, formerly bishop of Constantinople, who became their accomplice and partisan, as well as those who persevere in his communion; FOR TO EMBRACE THE COMMUNION OF SOMEONE (a heretic), IS TO MERIT A SIMILAR FATE (the anathema).”)

So Patriarch Msgr. Acacius was not heretical, but only was he anathematized for his communion, his friendly relations, his agreements with a deviant doctrinal policy (Henotikon), heretical therefore, cause of schism.

9.5.1. This Formula is of great authority according to the ordinary and universal magisterium of the Church. It meets the criterion of Saint Vincent of Lérins: “Quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus” (What has been believed everywhere, always, by all, belongs to the deposit of faith). Msgr. Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, in his Defensio Declarationis Cleri Gallicani (Book X, Chapter 7), states that this Formula was used in the following centuries with the same introduction and conclusion, adapted to new heresies and heretics, and that the bishops addressed it to popes like Hormisdas, Agapitus, Nicholas I and Adrian II during the Eighth Ecumenical Council (Constantinople IV, 869-870).

Bossuet emphasizes that what has been spread everywhere, propagated in all centuries and consecrated by an ecumenical council cannot be rejected by any Christian.

This confirms its certainty as a guide: it prohibits any contact with heretics that is not oriented toward their conversion, echoing 2 John 1:10-11: “If anyone comes to you and does not bring this doctrine, do not receive him into your house and do not say hello to him; for he who says hello to him participates in his evil works.”

In the context of semi-heresy, this Formula serves as a guide for behavior: he who maintains communion with heretics, without requiring their conversion, shares their fate (the anathema), even if he is not formally heretical. This applies to semi-heretics, who favor heresy by ambiguity or compromise.

Counter-arguments claiming that the Formula is purely historical and not binding for contemporary situations are refuted by its repeated use in councils and its universal application, as taught by Bossuet; this is not a subjective interpretation, but an objective doctrine that punishes any complicity with heresy. In short, the Formula, pontifical profession of faith, received and reused, enjoys a very high authority; several theologians support its infallible character by its insertion in constant teaching.

9.5.2. Application to Contemporary Situations from the Sedevacantist Point of View

From the sedevacantist point of view semi-heresy is evident in contemporary groupings that seek compromises with what is considered apostate Rome. The pre-1963 teaching, including Cum ex apostolatus officio (Pope Paul IV, 1559), affirms that a heretic automatically loses his office, without formal declaration. Sedevacantism argues that the “popes” post-1963 have undergone this fate by public heresies, as in the documents of Vatican II, and that any recognition of them implies a semi-heresy.

9.5.3. The example of the FSSPX

A prominent current example is the Society of Saint Pius X (FSSPX), under the direction of Msgr. Fellay, who seeks agreements with what sedevacantists consider heretical Rome. There are four agreements: Fellay as judge in Rome; jurisdiction for confession, marriages and for ordinations. These are communion with heretics, falling under the anathema of the Formula of Hormisdas, because they do not require conversion.

Counter-arguments, such as those affirming that these agreements are purely practical and without doctrinal compromise, are refuted by Scripture (2 Jn 1:10-11) and Bossuet’s interpretation of the Formula, which condemns any contact without conversion purpose. Sedevacantism refutes this by pointing to the infallible promise that the gates of hell will not prevail (Mt 16:18), implying that a “Rome” heretical is not the true Church. Still, it is necessary to distinguish between material and formal communion by the different members of the FSSPX.

Moreover, figures like John XXIII (1958) are seen as semi-heretical by suspicions under Pius XII, without formal condemnation, and his choice of name echoing an antipope. The retrospective view clearly reveals an ambiguity favoring modernism.

9.6. Refutation of Counter-Arguments

Counter-arguments often affirm that semi-heresy is subjective or that intentions excuse it. This is invalidated by the objective criteria of councils: intentions do not matter if the position favors heresy. Political contexts, like under Justinian, change nothing to the theological condemnation. Indeed the absence of bad intention does not excuse the objectivity of the error nor its danger; but pertinacity remains the dividing line of formal heresy.

Sedevacantism refutes the “recognize and resist” positions (like the FSSPX) as incoherent, because they recognize a heretic as pope, contradicting the pre-1963 teaching that heretics have no jurisdiction. The Formula of Hormisdas reinforces this: communion with heretics leads to the same fate, without exception for “good intentions.”

9.7. Brief

Semi-heresy is classically the position of a baptized person who does not profess a “propositio haeretica” with pertinacity, and who is not formally heretical; depending on the cases, he can fall under “temeraria,” “suspecta,” etc. As a weakening of orthodoxy, semi-heresy is a persistent danger, condemned by the Church many times. From the sedevacantist point of view, it is appropriate to avoid any compromise with contemporary errors, under penalty of anathema. The infallible Formula of Pope Hormisdas offers a clear guide in this matter. Tradition requires vigilance to preserve pure doctrine. As long as a baptized person does not profess a “propositio haeretica” with pertinacity, he is not formally heretical; depending on the cases, it can fall under “temeraria,” “suspecta,” etc. ‘Semi-heresy’ is a term of historico-polemical usage; if you want the technical censures remain those of the manuals (propositio haeretica, proxima haeresi, temeraria, suspecta, male sonans, etc.).

- The Bull Cum ex apostolatus officio

10.1. Its Text

Promulgated on February 15, 1559 by Paul IV, in a context of Protestant threat, the bull aims to prevent the infiltration of heretics into ecclesiastical offices. The key passage (§ 3, extract) stipulates: “Sancimus, statuimus, decernimus, et definimus, quod[…] omnes, et singuli Episcopi, Archiepiscopi, Patriarchae, Primates, Cardinales[…] qui hactenus[…] deviasse, aut in haeresim incidisse[…] deprehensi, aut confessi, vel convicti fuerint[…] et in posterum deviabunt, aut in haeresim incident[…] ipso facto, et absque aliqua iuris, aut facti declaratione, omnino, et penitus a suis[…] dignitate[…] officio[…] privatos omnino esse, et fore.” Fluid translation: “We add and declare that if ever it happened that a bishop, even acting as archbishop, patriarch, primate or cardinal of the Holy Roman Church, or legate, or even the Roman Pontiff, before his promotion or elevation to the cardinalate or pontificate, has deviated from the Catholic faith or fallen into heresy, his promotion or elevation, even if it has been made with the unanimous agreement and consent of all the cardinals, is null and void, and no right can be acquired by him who has been thus promoted or elevated, even if he has obtained peacefully the possession of this dignity or office.”

In § 6, the bull specifies: “Si quilibet[…] in haeresim inciderit[…] ipso facto, et absque aliqua declaratione, privatus existat.” Fluid translation: “whosoever falls into heresy is, by full right and without any declaration, immediately deprived of his dignity and office.”

The bull seems to include any public heresy without explicit distinction between formal and material, which requires clarification to harmonize with traditional doctrine.

10.2. Reconciliation with Traditional Doctrine

Catholic doctrine clearly distinguishes formal heresy from material heresy, and the bull fits into this theological framework. The following points reconcile the bull with the doctrine:

10.2.A. Presumption of Pertinacity: A public heresy is presumed pertinacious, especially in a cleric, bound to know the faith.

A.1. All: Saint Thomas extends this to all (Summa Theologica, I-II, q. 76, a. 2): “everyone is bound to know in general the truths of faith and the universal precepts of law, and each in particular is bound to know what regards his state or function.”

A.2. The Clerics: Wernz–Vidal, Ius Canonicum, t. VII: “Clerici, qui in sacris disciplinis sunt instituti et fidei doctores esse debent, ignorantia fidei excusari non possunt.” (“Clerics, trained in sacred disciplines and called to be doctors of the faith, cannot be excused by ignorance in matters of faith.”)

This is a rule that is broader than for the matter of heresy, it applies to all dol or fraud, so it behaves like a principle of law: Code of Canon Law of 1917, canon 2200 § 2, establishes a general principle “Posita externa legis violatione, dolus in foro externo praesumitur, donec contrarium probetur.” (“The external violation of the law being posed, dol is presumed in the external forum until proven otherwise.”) Perversion — of faith — heresy: violation — of law — dol.

Heresy is like a dol of violation of the law of faith. The law or rule of faith is that one must believe everything that is revealed.

This is in accordance with Catholic doctrine, which stipulates that clerics, as pastors of the faithful, are held to a higher standard of knowledge and responsibility. Cf. Ezekiel 33:6: “Si autem speculator viderit gladium venientem, et non insonuerit tuba[…] sanguinem ejus de manu speculatoris requiram” — (“But if the watchman sees the sword coming and does not sound the trumpet[…] I will require his blood from the watchman’s hand.”)

This presumption is rebuttable: if the individual proves invincible ignorance, his error is material, and the ipso facto sanctions do not apply.

Canon 2199: “The imputability of the offense depends on the dol of the delinquent or on his culpability in the ignorance of the violated law or in the omission of the necessary diligence: consequently, all causes that increase, diminish, suppress the dol or culpability, increase, diminish, suppress by the fact the imputability of the offense.”

This canon establishes that for a penal sanction to apply, a voluntary fault is required, which excludes invincible ignorance.

Canon 2202: § 1. Violatio legis ignoratae nullatenus imputatur, si ignorantia fuerit inculpabilis; secus imputabilitas minuitur plus minusve pro ignorantiae ipsius culpabilitate. (§ 1. The violation of an ignored law is in no way imputed if the ignorance is not culpable; in the opposite case, imputability is diminished more or less according to the culpability of the ignorance itself.)

- 2. Ignorantia solius poenae imputabilitatem delicti non tollit, sed aliquantum minuit. (§ 2. Ignorance of the penalty alone does not suppress the imputability of the offense, but diminishes it to some extent.)

- 3. Quae de ignorantia statuuntur, valent quoque de inadvertentia et errore. (§ 3. What is established about ignorance also applies to inadvertence and error.)

10.2.B. Material Heretic and Sanctions: See section 4 above.

10.2.C. Context of the Bull:

The bull targets manifest heretics, whose public and notorious error presumes a voluntary opposition to the faith. Thus demonstrated by Bellarmine (De Romano Pontifice, book II, cap. 30) that a public heretic, especially a cleric, loses his office ipso facto without formal declaration, because his error breaks communion with the Church.

- Practical Distinction between Formal Heretic and Material

In practice, distinguishing a formal heretic from a material heretic in case of public heresy relies on objective criteria in the external forum, without claiming to judge internal intentions. Here are the practical steps, ordered to reflect the ecclesiastical process:

11.1. Verification of the Error:

The error must concern a defined divine and Catholic truth of faith (de fide definita), like the divinity of Christ (Council of Nicaea, 325) or pontifical infallibility (Vatican I, Dei Filius, 1870, cap. 3). An error on a non-defined doctrine can be proxima haeresi or temeraria, but not heretical in the strict sense (Tanquerey, Synopsis Theologiae Dogmaticae, t. I). Example: Affirming that “all religions lead to salvation” contradicts Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus (Council of Florence, 1442, Denzinger, no. 802), constituting an objective heresy.

11.2. Evaluation of Publicity:

The error is public if expressed by notorious words, writings or acts, known to a significant number of people. An occult error (kept in conscience) does not pertain to the external forum and does not entail sanctions from the Church (see Prümmer, Manuale Theologiae Moralis, 1931, t. I).

11.3 Canonical Admonition:

According to the 1917 Code, a person suspected of heresy must be formally admonished by ecclesiastical authority (bishop or competent superior) to establish pertinacity. Two admonitions are generally required, unless the heresy is notoriously obstinate (repeated after public correction). Epistle of St Paul to Titus 3:10-11 (Vulgate): “Haereticum hominem post primam et secundam correptionem devita, sciens quia subversus est qui eiusmodi est, et peccat, cum sit proprio iudicio condemnatus.” Translation into English: “As for the heretical man, after a first and second admonition, reject him, knowing that such a man is perverted and sins, being condemned by his own judgment.”

If the individual corrects himself after admonition, his error was material, and he avoids ipso facto sanctions. If he persists, his heresy becomes formal, entailing excommunication and loss of office ipso facto.

11.4. Context and Circumstances:

– Formation: A cleric (priest, bishop) is presumed to know the truths of faith, making invincible ignorance improbable. Bellarmine (op. cit., cap. 30) notes that the public heresy of a cleric is almost always formal.

– Behavior: A desire for correction or expressed ignorance indicates material heresy. An obstinate refusal (for example, repeated after admonition) establishes pertinacity.

– Scandal: If the public error of a material heretic disturbs the faithful, disciplinary measures (ferendae sententiae), like a suspension, can be imposed, without presuming excommunication (Billot, op. cit.).

11.5. Practical Example:

Suppose a priest publicly preaches that “every religion is good and sanctifying,” contradicting the dogma that there is no salvation outside the Church.

Here is how to proceed:

– Step 1: Identify the error. This proposition is objectively heretical, if it denies a defined truth.

– Step 2: Ascertain publicity. If the preach is given in public or published, the error is public.

– Step 3: Admonition. The bishop admonishes the priest, explaining the error and requiring a retraction. If the priest corrects himself, his error was material, and he remains in communion. If he persists, his heresy becomes formal, entailing excommunication (Code, canon 2314 § 1) and loss of office (Code, canon 188 § 4).

– Step 4: Immediate Measures. If the error causes a scandal, the priest can be suspended immediately (ferendae sententiae) to protect the faithful, even if he is material, pending the admonition. The faithful must avoid such a priest so as not to participate in his scandal (2 John 1:10-11).

- Current Catholic Perspective (Sedevacantist)

In the current crisis, the public heresies of Vatican II (for example, religious liberty or ecumenism) are considered formal, because they contradict defined dogmas (Syllabus Errorum, Pius IX, 1864, prop. 16) and persist despite warnings from the faithful, priests and especially bishops who have kept the faith. According to Cum ex apostolatus officio (§ 6), the occupants of the See of Peter, by professing these manifest heresies, have lost their office ipso facto, without formal declaration.

- Counter-Arguments and Refutation

13.1. The bull includes material heresy, because it speaks of “some heresy” without distinction.

Refutation: The bull targets manifest heretics (“deprehensi, confessi, vel convicti”), implying a voluntary opposition. Bellarmine (op. cit.) and Wernz-Vidal (op. cit.) confirm that ipso facto sanctions apply to public formal heresy, not to involuntary material error.

13.2. Without legitimate authority post-1963, admonition is impossible.

Refutation: In the current crisis, the heresies of Vatican II are notoriously pertinacious because of their public persistence and their rejection of Catholic warnings.

- Conclusion

The Formula of Hormisdas (515, Denzinger, no. 363) warns: “Nos pariter Acacium[…] anathematizamus[…] quia communionem alicuius amplexari, similem mereri sortem est.” (“We anathematize Acacius[…] for to embrace the communion of someone (that is, a heretic), is to merit a similar fate (in this historical case: excommunication).”) The faithful must avoid those who propagate public heresy, in accordance with 2 John 1:10-11, relying on objective criteria in the external forum.

Formal heresy is a conscious revolt against a dogma, punished by excommunication and removal; material heresy is an involuntary error, without automatic sanctions. The material heretic does not lose his office “ipso facto” nor is he excommunicated “latae sententiae,” but if he publicly propagates his error, he must be corrected or suspended to protect the faithful, unless his pertinacity is not established.

In canonical praxis, if there is ascertained public defection, the cause is treated in the external forum, independently of internal psychology.

This development clarifies that the material heretic escapes automatic sanctions, but may be subject to disciplinary measures if his error becomes public and risks harming the Church, in line with immutable doctrine.

A public heresy indeed entails ipso facto sanctions (excommunication and loss of office) for the manifest formal heretic, because publicity presumes pertinacity (1917 Code, canon 2200 § 2).

- Sources

– 1917 Code of Canon Law, canons 188 § 4, 2200 § 2, 2314 § 1, 2316, 1325,

2314, 188, 2264, 2315, 2316, 2261.

– Paul IV, Cum ex apostolatus officio, February 15, 1559 (Magnum Bullarium Romanum,

- IV, p. 354 sqq.).

– Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II-II, q. 11; q. 5, a. 3; q. 11, a. 3; I-II,

- 76, a. 2; II-II, q. 4, a. 1.

– Bellarmine, De Romano Pontifice, book II, cap. 30.

– Billot, De Ecclesia Christi, 1927, t. I; 1910, t. I.

– Franzelin, Theses de Ecclesia Christi, 1876; De Divina Traditione et Scriptura,

Rome 1875.

– Wernz-Vidal, Ius Canonicum, 1933, t. VII.

– Van Noort, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, 1920; De vera religione, cap. II.

– Tanquerey, Synopsis Theologiae Dogmaticae, t. I; t. III, n. 1245.

– Prümmer, Manuale Theologiae Moralis, 1931, t. I.

– Denzinger, Enchiridion symbolorum, no. 802 (Council of Florence, 1442), no. 363

(Formula of Hormisdas, 519); no. 3020; DS 3011; 2420 sqq.; 2598; 3050

sqq.

– Pius IX, Syllabus Errorum, December 8, 1864, prop. 16; prop. 80.

– Council of Trent, Sess. XXIV, can. 1, 1563; Sess. VI, can. 9.

– Dictionary of Catholic Theology, art. Heresy (ed. 1912).

– Pius X, Pascendi Dominici gregis, 1907.

– Cajetan, Tractatus de Fide, 1530.

– Hurter, Compendium Theologiae Dogmaticae, 1907, t. III.

– Theologia Wirceburgensis, 1880, t. I.

– Saint Augustine, Contra Faustum, XX.

– Vatican I, Dei Filius, cap. 3-4.

– Adolphe Tanquerey, Synopsis theologiae dogmaticae, t. I, t. III.

– Billuart, De Virtutibus Theologicis, Dissert. V, art. 3; De Fide, diss. IV.

– Jean de Saint-Thomas, Cursus Theologicus, t. I; disp. 20.

– Melchior Cano, De locis theologicis, lib. XII.

– Pius X, Lamentabili Sane, 1907, prop. 25.

– Unigenitus, 1713.

– Auctorem fidei, 1794.

– Leo XIII, Officiorum ac Munerum, 1897.

– Leo XIII, Immortale Dei, 1885.

– Pesch, Praelectiones dogmaticae, I.

– Gousset, Théologie morale, I, ch. IV.

– Msgr. G. Van der Vorst, Institutiones Theologiae Fundamentalis, 1923.

– Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913, art. Heresy; art. Semipelagianism; art. Arianism.

– Bossuet, Defensio Declarationis Cleri Gallicani, Livre X, Chapitre 7.

– Saint Vincent de Lérins, Commonitorium.

– Gratian, Decretum, C. 24, q. 1.

– Catechism of the Council of Trent, on the 1st and 2nd Commandment.

– S. Alphonsus, Theologia Moralis, lib. IV.

– S. Alphonse, Theologia Moralis, lib. IV.

– Van Noort, De vera religione, cap. II.